What is the Japanese Tachi?

TLDR: A Japanese tachi is a traditional, slightly curved sword worn edge-down by samurai, predating the katana and known for its longer blade and ornate fittings.

The Japanese tachi is a masterpiece of sword craftsmanship that predates the more widely known katana. This elegant, curved blade holds a special place in the hearts of those who appreciate the artistry and history of Japanese swords. When you first lay eyes on a tachi, you’re struck by its graceful curve and the way it seems to embody the spirit of the samurai who once wielded it.

Historically, the tachi was the primary sword of Japan’s mounted warriors during the Heian and Kamakura periods. Its longer, more curved blade made it ideal for slashing attacks from horseback. But the tachi is more than just a weapon; it’s a symbol of Japan’s rich martial heritage and a testament to the skill of the swordsmiths who forged it.

In my opinion, what makes the tachi truly fascinating is how it reflects the evolution of Japanese sword-making techniques. Each tachi tells a story, not just of battles fought, but of the craftsmen who poured their expertise into creating these blades. From the distinctive curvature to the intricate fittings, every aspect of the tachi is a window into Japan’s past.

Origins and History of the Japanese Tachi

The tachi’s story begins in the Heian period (794-1185), a time of cultural refinement and artistic flourishing in Japan. It’s during this era that we see the emergence of the distinctive curved blade that would become the tachi’s hallmark. Holding a well-preserved Heian-era tachi is like touching a piece of living history – you can almost feel the centuries of tradition flowing through the steel.

Early tachi were heavily influenced by Chinese and Korean sword-making techniques. Japanese swordsmiths, always eager to refine their craft, incorporated elements from these continental styles. The result was a uniquely Japanese weapon that combined the best of multiple sword-making traditions. You can see this fusion in the blade’s curvature and the heat-treating techniques used to create the legendary hamon (temper line).

As we move through different periods, the tachi evolved alongside Japanese warfare and culture. During the Kamakura period (1185-1333), tachi became longer and more curved, optimized for mounted combat. The Nanbokucho period (1336-1392) saw the emergence of the ō-dachi, or “great tachi,” some reaching over 3 feet in blade length. These massive swords are awe-inspiring to behold, though I can’t imagine they were very practical in actual combat.

By the Muromachi period (1336-1573), we start to see the transition from tachi to katana. This shift reflects changes in warfare, with infantry becoming more prominent than cavalry. The tachi, however, never completely disappeared. Even as the katana rose to prominence, tachi continued to be made and prized, especially for ceremonial purposes.

In my opinion, what’s most fascinating about the tachi’s evolution is how it mirrors the broader changes in Japanese society. From the refined court culture of the Heian period to the tumultuous wars of the later eras, the tachi adapted and endured. Each period left its mark on the design and craftsmanship of these blades, creating a rich tapestry of styles and techniques that sword enthusiasts still study and admire today.

Japanese Tachi Design and Characteristics

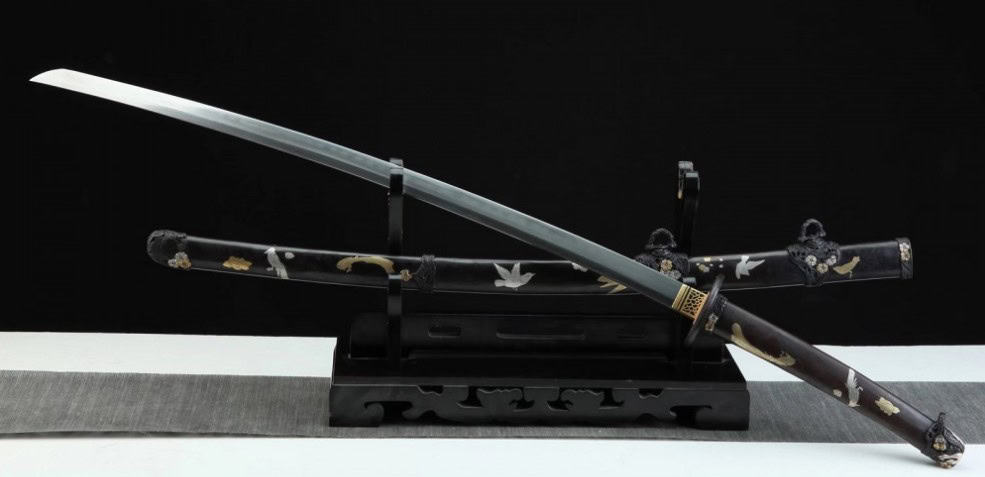

The design of the Japanese tachi is a marvel of form and function, embodying the elegance and efficiency that define Japanese sword craftsmanship. One of the most striking features of the tachi is its curved blade. This curvature, known as “sori,” is more pronounced than that of the katana, giving the tachi its distinctive sweeping arc. This design isn’t just for aesthetics; it enhances the sword’s cutting ability, especially in slashing attacks from horseback. There’s something incredibly satisfying about the fluidity and grace of a well-crafted tachi’s curve.

How Long is a Tachi?

Regarding length, tachi blades are typically longer than katana blades, often measuring between 70 to 80 centimeters. This extra length, combined with the curvature, makes the tachi ideal for mounted combat, allowing the wielder to deliver powerful, sweeping strikes. When you compare a tachi to a katana, the differences are clear – the katana’s straighter, shorter blade is optimized for quick, precise cuts, while the tachi’s design favors broader, more forceful movements.

The key components of a tachi are a testament to the meticulous attention to detail that goes into each sword. The blade, or “nagasa,” is the heart of the tachi, forged with a combination of hard and soft steel to create a resilient yet sharp edge. The tsuba, or handguard, is often more ornate than those found on katanas, reflecting the tachi’s status as both a weapon and a work of art. The saya, or scabbard, is typically lacquered and decorated, providing both protection and a touch of elegance.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the tachi’s design is the way it is worn. Unlike the katana, which is worn edge-up, the tachi is traditionally worn edge-down, suspended from the belt by cords. This difference in wearing style is more than just a matter of tradition; it affects the way the sword is drawn and used in combat. Drawing a tachi involves a sweeping motion that complements its curved blade, allowing for a fluid transition from draw to strike.

The materials used in crafting a tachi are as important as the design itself. Traditional tachi are made from tamahagane, a type of high-quality steel produced from iron sand. This steel is folded and forged repeatedly to create a blade that is both strong and flexible. The hilt, or “tsuka,” is often wrapped in rayskin and silk, providing a secure grip and a touch of luxury. The fittings, including the tsuba and other metal components, are usually made from iron, copper, or brass, and are often intricately decorated with motifs that reflect the sword’s cultural significance.

Japanese Tachi Craftsmanship

The craftsmanship behind the Japanese tachi is nothing short of awe-inspiring. Traditional forging techniques used to create these blades are a perfect blend of science and art, passed down through generations of master swordsmiths. The process begins with the careful selection of tamahagane, the high-carbon steel that forms the core of the blade. Watching a skilled smith fold and hammer this steel, sometimes up to 16 times, is like witnessing alchemy in action. Each fold removes impurities and creates the distinctive grain pattern that gives Japanese swords their unique beauty.

One of the most crucial steps in forging a tachi is the differential hardening process, which creates the famous hamon (temper line). The smith coats the blade with clay, thicker on the spine and thinner on the edge, before quenching it in water. This technique results in a hard, sharp edge and a more flexible spine – the perfect combination for a battle-ready sword. The patterns formed in the hamon are like fingerprints, unique to each blade and smith.

When it comes to notable swordsmiths, names like Yasutsuna, Masamune, and Muramasa are spoken with reverence among sword enthusiasts. Yasutsuna, active in the late Heian period, is credited with creating some of the earliest tachi. His blades are characterized by a deep curvature and exquisite craftsmanship. Masamune, often considered the greatest swordsmith in Japanese history, was known for blades of unparalleled beauty and quality. His tachi are said to have a spiritual quality, embodying the samurai virtues of loyalty and honor. Muramasa, while controversial due to legends surrounding his blades’ bloodthirst, created tachi of exceptional sharpness and durability.

The regional styles and schools of swordsmithing add another layer of fascination to tachi craftsmanship. The Bizen tradition, originating from modern-day Okayama Prefecture, is known for its distinctive mokume-hada (wood-grain pattern) and gunome-midare hamon. Yamashiro blades, from the area around Kyoto, are prized for their elegant and refined appearance, often featuring a straight hamon. The Soshu school, founded by Masamune, combines elements of both Bizen and Yamashiro styles, resulting in blades of exceptional quality and beauty.

Types of Japanese Tachi

When it comes to tachi, the variety in styles and designs is truly fascinating. One of the most interesting aspects is how the blade curvature can significantly affect both the sword’s appearance and its performance in combat. The two main classifications based on blade curvature are koshizori and toriizori.

Koshizori tachi have a curve that’s more pronounced near the hilt, giving the blade a graceful, sweeping arc. This design is particularly effective for mounted combat, allowing for powerful slashing attacks from horseback. Holding a koshizori tachi, you can feel how the balance and curve work together to create a fluid, natural cutting motion.

Toriizori tachi, on the other hand, have a more uniform curve along the entire length of the blade. This style became more popular in later periods and is often seen as a transitional form between early tachi and the straighter katana. In my experience, toriizori tachi offer a nice balance between the traditional tachi design and the versatility needed for infantry combat.

When it comes to mounting styles, the variations can be just as intriguing as the blade types. The Kuro Urushi Tachi, with its black lacquered scabbard, is a personal favorite. The deep, glossy black not only looks stunning but also serves a practical purpose, protecting the saya from moisture and wear. These tachi were often used in formal court settings, and you can imagine the impressive sight they must have made.

The Hyogo Kusari Tachi is another remarkable variation. This style features a chain attached to the scabbard, which could be used to secure the sword to the wearer’s armor. It’s a clever design that speaks to the practical considerations of samurai in full battle gear. Examining a well-preserved Hyogo Kusari Tachi gives you a real sense of the ingenuity of Japanese sword makers and how they adapted their designs to meet the needs of warriors.

Other mounting styles include the Shiromaki Tachi, with its white-wrapped hilt and scabbard, and the Aoi Tachi, which features hollyhock-shaped ornaments. Each style has its own unique aesthetic and historical significance, making the study of tachi variations an endless source of fascination.

Tachi vs. Katana

The comparison between the tachi and the katana is a topic that never fails to spark lively discussions among sword enthusiasts. While both are iconic Japanese swords, they have distinct differences in design and use that reflect the changing needs and tactics of samurai warriors over the centuries.

The most immediate difference you’ll notice is how the two swords are worn. The tachi is traditionally worn edge-down, suspended from the belt by cords, which makes it ideal for drawing and cutting in a single, fluid motion while mounted. The katana, on the other hand, is worn edge-up, tucked into the obi (belt). This positioning allows for a quicker draw and strike, which is particularly useful in close-quarters combat.

In terms of design, the tachi typically has a more pronounced curvature (sori) than the katana. This curvature is not just for aesthetics; it enhances the sword’s effectiveness in slashing attacks, especially from horseback. The katana, with its slightly straighter blade, is optimized for quick, precise cuts. This design evolution reflects a shift from mounted to infantry combat, where the ability to draw and strike swiftly became more critical.

Another key difference lies in the length and balance of the blades. Tachi are generally longer, often measuring between 70 to 80 centimeters, and are balanced to be wielded with one or two hands. The katana is usually slightly shorter and lighter, designed for one-handed use, which allows for greater maneuverability and speed. Holding a tachi, you can feel the weight and balance that make it perfect for powerful, sweeping strikes. In contrast, the katana feels nimble and responsive, ideal for rapid, precise movements.

The transition from tachi to katana began during the Muromachi period (1336-1573) and was largely driven by changes in warfare. As samurai began to fight more frequently on foot, the need for a sword that could be quickly drawn and used in close combat became apparent. The katana’s design, with its edge-up carry and slightly straighter blade, met these new requirements perfectly. By the end of the 16th century, the katana had largely supplanted the tachi as the primary weapon of the samurai.

Where Can I Get My Own Japanese Tachi?

Acquiring a Japanese tachi involves finding a balance between authenticity, craftsmanship, and budget. Reputable sources include specialized sword shops in Japan, which offer both antique and newly crafted blades. Online retailers and auction sites also provide access to a range of options, but it’s crucial to verify the seller’s credibility to ensure you’re purchasing a genuine piece.

HanBon Forge

What I Like:

- Material Quality: The sword features Damascus folded steel with clay tempering, providing both beauty and durability.

- Craftsmanship Details: The full tang blade is secured with two bamboo mekugi, and the handle includes brass components and real ray skin wrapping for a traditional look and feel.

- Additional Accessories: The sword comes with a three-color copper saya, a free sword bag, and a certificate of authenticity, enhancing its value and presentation.

TrueKatana

What I Like:

- Damascus steel full tang blade with real hamon: The hand-sharpened blade, made from Damascus steel, showcases strength and elegance with its distinctive water-like patterns and clay-tempered hamon.

- Green cord handle with real white samegawa: The handle, wrapped in a green cord over genuine white samegawa, offers an exceptional grip and a striking look.

- Brown hardwood saya with premium natural lacquer: The saya, made from robust hardwood and coated with premium natural lacquer, has a deep brown hue that enhances its visual appeal and durability.

Samurai Sword Store

What I Like:

- Blade Material: The sword is made from hand-forged 1060 carbon steel, ensuring durability and sharpness for cutting soft and medium-density targets.

- Construction: It features a full tang design, meaning the tang is forged as one piece with the blade for added strength and balance.

- Aesthetic Details: The sword includes elegant metal fittings and a white and grey hardwood saya, along with a white ray skin wrap and silk sword bag for a visually striking presentation.

Final Thoughts

In exploring the tachi, it’s clear that this elegant blade offers a captivating glimpse into the evolution of Japanese sword craftsmanship. From its origins in the Heian period to its transition towards the katana in the Muromachi period, the tachi reflects the changing needs and tactics of the samurai. I particularly appreciate the pronounced curvature and the historical significance of how these swords were worn edge-down, showcasing a seamless blend of form and function. It’s fascinating to compare the tachi to other historical blades, such as the types of Chinese swords, which also highlight unique cultural approaches to weapon design and martial traditions.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, which means if you click and buy something, we get a tiny commission—like a virtual high-five in cash form (don’t worry, it costs you nothing).