How Early Chinese Swords Shaped a Culture

TLDR: Early Chinese swords, particularly the Jian and Dao, played a crucial role in shaping military strategies and social hierarchies. The Jian emerged as a prominent weapon during the Warring States Period, while the Dao gained popularity in the Han Dynasty, influencing combat styles and daily life.

The story of early Chinese swords is a fascinating journey through time, reflecting the evolution of weaponry and its profound impact on society. From the prehistoric origins of simple stone and bronze blades to the sophisticated designs of the Jian and Dao, these swords played crucial roles in shaping military strategies and social hierarchies. I find it intriguing how these weapons were not merely tools for battle; they were pivotal in defining status and identity among warriors. Understanding the development of these swords offers a glimpse into the complexities of ancient Chinese civilization and its martial traditions.

Development of Early Chinese Swords

The origins of early Chinese swords can be traced back to prehistoric times, where the earliest weapons were crafted from stone and later evolved into bronze. Initially, these primitive weapons were simple in design, primarily used for thrusting rather than cutting. The transition from rudimentary stone tools to more sophisticated bronze blades marked a significant technological advancement in ancient China. This evolution was driven by the need for more effective weaponry as societies became increasingly organized and engaged in conflicts.

As the Bronze Age progressed, the use of bronze materials became prominent in sword-making. The introduction of bronze allowed for the creation of longer and more durable blades, which were essential for both hunting and warfare. Early bronze swords often featured double-edged designs, enhancing their effectiveness in combat. The transition from simple weapons to complex designs reflected the growing sophistication of ancient Chinese society and its understanding of metallurgy.

During the Bronze Age, particularly around 1200 BC during the Shang Dynasty, the characteristics of early bronze swords began to evolve significantly. These swords were typically longer than their predecessors and featured intricate designs that showcased the craftsmanship of ancient artisans. Innovations in metallurgy during this period led to the development of high-tin bronze, which provided greater hardness compared to lower-tin alloys used elsewhere. This allowed for sharper edges but also made the blades more prone to breaking under stress.

The pinnacle of sword-making technology was reached during the Warring States period (475–221 BC), where advancements included casting techniques that allowed for unique designs such as laminated blades and complex patterns on the surface. One notable example is the Sword of Goujian, renowned for its sharpness and resistance to corrosion, which exemplifies the high level of skill achieved by Chinese swordsmiths at that time. The combination of artistic expression and functional design in these swords not only enhanced their combat effectiveness but also established them as symbols of power and prestige among warriors.

The Warring States Period and the Jian

The Warring States Period (475-221 BC) marked a significant era in the evolution of Chinese weaponry, particularly with the emergence of the Jian as a prominent weapon. During this time, the Jian underwent substantial refinements in design and functionality, establishing itself as a formidable tool in both warfare and personal combat.

The Jian of this period featured a double-edged, straight blade typically ranging from 70 to 100 cm in length. Its design incorporated a guard, often shaped like a pair of wings pointing up or down, which protected the user’s hand. The Jian’s pommel, located at the end of the handle, provided balance and could be used as a secondary striking point. These design features contributed to the Jian’s versatility and effectiveness in combat.

One of the key advantages of the Jian was its construction material. While many contemporary weapons were still made of bronze, the Jian was crafted from forged steel, making it more durable and less prone to damage. This superior metallurgy, combined with its relatively light weight of 1.5 to 2 pounds for a typical 28-inch blade, allowed for improved mobility and agility in combat.

The tactical uses of the Jian in warfare and personal combat were diverse. Its design allowed for both thrusting and slashing techniques, making it effective in close-quarters combat. The Jian’s versatility is evident in its blade structure: the bottom third was fairly blunt for defensive actions, the middle third somewhat sharper for a variety of offensive and defensive moves, and the top third very sharp for precise attacks.

The influence of the Jian on military strategy and tactics during the Warring States Period was significant. Its effectiveness in both offensive and defensive maneuvers led to changes in battlefield formations. The Jian’s versatility allowed for more flexible tactical approaches, as soldiers could quickly switch between thrusting and slashing techniques based on the situation.

Skilled swordsmen wielding the Jian played a crucial role in military success. Their ability to execute complex techniques and adapt to various combat scenarios made them valuable assets on the battlefield. The importance of these skilled warriors is reflected in the development of test cutting practices known as shizhan, where swordsmen honed their skills on targets made from bamboo, rice straw, or saplings.

The Rise of the Dao During the Han Dynasty

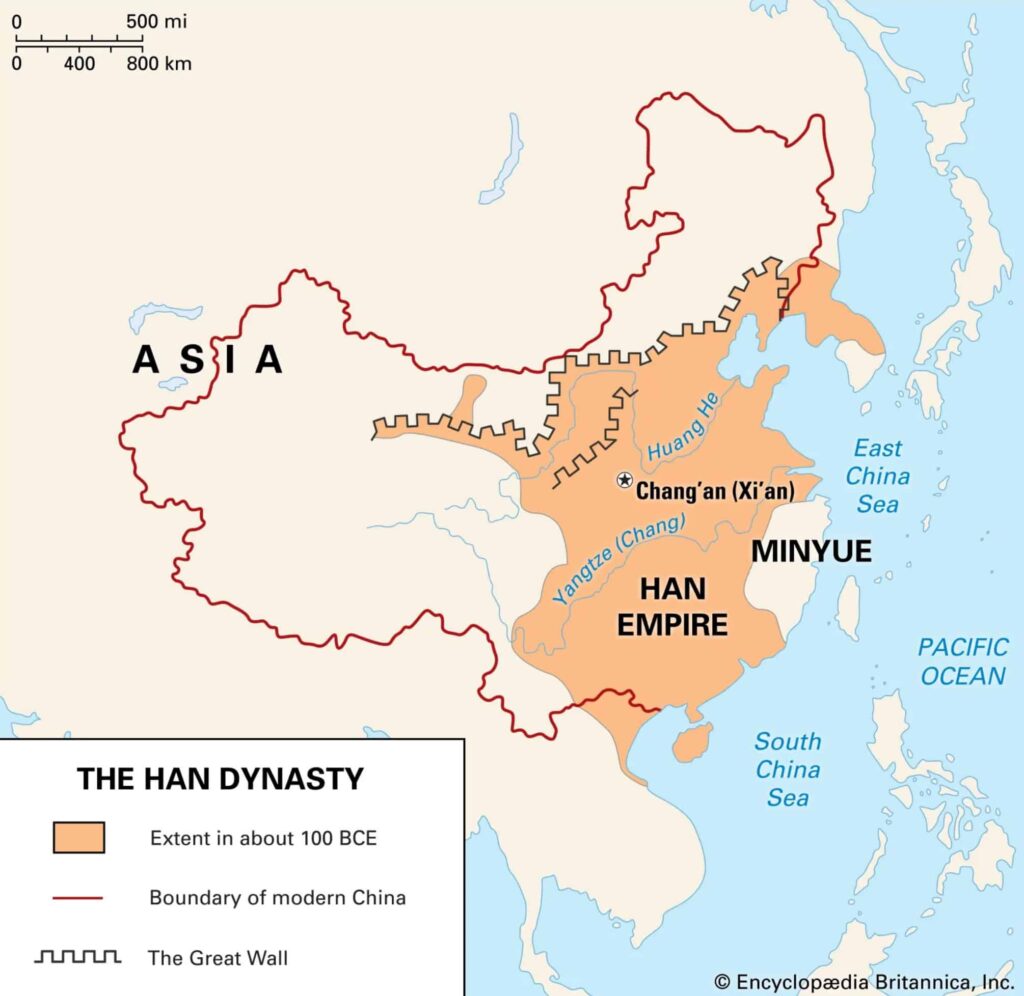

The Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) marked a significant period in the evolution of Chinese swords, particularly with the rise of the Dao. This single-edged sword gained prominence during this era, gradually overshadowing its predecessor, the Jian.

The Dao’s design differed significantly from the Jian, reflecting a shift in combat needs and metallurgical advancements. Unlike the straight, double-edged Jian, the Dao featured a single-edged blade that was often curved, especially in later designs. This curvature allowed for more effective slashing and chopping motions. The Dao’s blade was typically thicker along the spine, providing greater durability and making it less prone to breaking during intense combat.

One distinctive feature of early Han Dynasty Dao swords was the ring pommel, which became a standard design element. These swords were often shorter than Jian, with blades around two feet in length, making them more maneuverable in close-quarter combat. The single edge allowed for a more robust construction, as the blunt back could be thickened for added strength without compromising the sword’s weight.

The Dao’s popularity among military units, especially cavalry, stemmed from its versatility and effectiveness. Its design was particularly suited for mounted combat, where the curved blade could deliver powerful slashing attacks from horseback. The sword’s durability and ease of use made it an ideal weapon for large-scale military operations, contributing to its widespread adoption.

The introduction of the Dao necessitated adaptations in fighting techniques. Its design favored slashing and chopping motions over the thrusting techniques commonly used with the Jian. This shift in combat style influenced military training and tactics, with a greater emphasis on powerful, sweeping attacks that could be effective against armored opponents.

The Dao’s influence extended beyond military use, impacting civilian self-defense and daily tasks. Its relatively simple design and straightforward use made it accessible to a broader population. The Dao became a popular choice for personal protection and was often used in sword dances, reflecting its integration into Chinese culture beyond warfare.

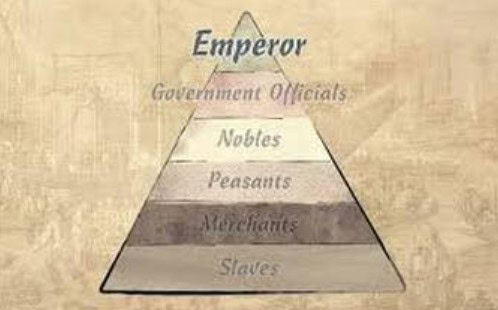

Social Hierarchies and Status Associated with Swords

In ancient China, swords played a crucial role in defining social hierarchies and status. The ownership of certain swords was a clear indicator of one’s position in society, with higher-quality and more intricately crafted blades signifying greater prestige. This association between swords and status was deeply ingrained in Chinese culture, influencing social dynamics and personal aspirations.

The quality and craftsmanship of a sword often reflected the owner’s rank and wealth. Nobles and high-ranking officials possessed swords made of the finest materials, adorned with precious metals and gemstones. These weapons were not just tools for combat but symbols of power and authority. In contrast, common soldiers and lower-ranking individuals typically owned simpler, less ornate swords.

Swords also played a role in social mobility, particularly among warriors. Skilled swordsmen could rise through the ranks based on their prowess in battle and mastery of the weapon. This potential for advancement through martial skill created a unique dynamic within the military hierarchy, where talent with a sword could sometimes overcome the limitations of one’s birth status.

The practice of gifting swords held significant importance in Chinese diplomacy and political alliances. High-quality swords were often presented as gifts to seal agreements or foster goodwill between states. These sword gifts carried deep symbolic meanings, representing trust, respect, and the transfer of power or authority. The act of gifting a sword could strengthen bonds between rulers or serve as a gesture of peace between formerly hostile parties.

| Sword Type | Social Significance |

| Ornate, gem-adorned | High nobility, royalty |

| Fine steel, well-crafted | Military officers, wealthy merchants |

| Simple, functional | Common soldiers, lower ranks |

The symbolic power of swords extended beyond their practical use, influencing literature and art. Poets and scholars often used sword imagery to express their aspirations and frustrations with their place in society. This cultural significance of swords fascinates me, particularly how a single object could embody so many aspects of Chinese social and political life.

I find it intriguing how the ownership and mastery of swords could sometimes transcend rigid social boundaries in ancient China. The idea that skill with a blade could potentially elevate one’s status adds a dynamic element to our understanding of historical social structures.

Final Thoughts

As we explore how early Chinese swords shaped society, it becomes clear that their influence extends far beyond the battlefield. The transition from the Jian’s tactical advantages during the Warring States Period to the Dao’s prominence in the Han Dynasty illustrates how weaponry can reflect and drive social change. I often marvel at how these swords served as symbols of power and status, affecting everything from military tactics to personal identity.