Chinese Sword Symbolism and Philosophy

TLDR: Chinese swordsmanship combines martial skill with deep philosophical teachings, emphasizing harmony, resilience, and ethical conduct. Legendary swords like Gan Jiang and Mo Ye symbolize unity, while the Sword of Goujian represents resilience.

You know, there’s something truly captivating about Chinese swords and the philosophy behind them. I’ve always been drawn to the way these blades aren’t just weapons, but carriers of deep wisdom and centuries of tradition. From the legendary Sword of Goujian to the poetic musings of Li Bai, Chinese swords weave a tapestry of history, lore, and philosophical thought that’s simply unmatched. I’m no expert, but I can’t help feeling that understanding these swords is like unlocking a secret door to ancient Chinese culture and wisdom.

Historical Development of Chinese Sword Philosophy

The historical development of Chinese sword philosophy is a fascinating journey that spans millennia, intertwining martial prowess with profound philosophical concepts. This evolution reflects the changing societal values and intellectual currents of ancient China.

The origins of sword philosophy can be traced back to the Neolithic period, where early influences began to shape the way swordsmanship was perceived and practiced. During this time, the use of weapons was likely tied to survival and tribal conflicts, but it also began to take on deeper meanings. As societies became more complex, so did the ideas surrounding swordsmanship. The integration of Daoist concepts, particularly “wu-wei” or effortless action, marked a significant shift in sword philosophy. This principle encouraged practitioners to move with natural fluidity, adapting to situations without forced effort – a concept that would profoundly influence Chinese martial arts for generations to come.

As dynasties rose and fell, the role and philosophy of swordsmanship evolved dramatically. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), swords began to transition from purely practical combat tools to objects of ceremonial significance. This trend continued into the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), where swordsmanship became increasingly associated with scholarly pursuits and artistic expression. The dao, or single-edged sword, gained prominence during this period, reflecting changing military tactics and philosophical ideals.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) saw a further shift in sword philosophy. As firearms became more prevalent on the battlefield, the practical military use of swords declined. However, this period witnessed a rise in scholarly swordsmanship, where the sword became a tool for self-cultivation and philosophical exploration. Ming-era texts reveal a sophisticated understanding of swordsmanship that went far beyond mere combat techniques.

Here’s a brief overview of the philosophical concepts that influenced Chinese swordsmanship across different periods:

| Period | Philosophical Influence | Key Concept |

| Neolithic | Early animism and tribal beliefs | Survival and power |

| Warring States | Daoism | Wu-wei (effortless action) |

| Han Dynasty | Confucianism | Moral cultivation |

| Tang Dynasty | Buddhism | Mind-body harmony |

| Ming Dynasty | Neo-Confucianism | Self-cultivation and scholarly pursuit |

I’ve always been captivated by the way Chinese sword philosophy seamlessly blends practical skills with profound wisdom. The idea that a warrior could embody both martial prowess and scholarly refinement is particularly intriguing to me. Personally, I find the concept of “wu-wei” in swordsmanship to be a powerful metaphor for navigating life’s challenges.

Philosophical Concepts Embedded in Swordsmanship

The philosophical concepts embedded in Chinese swordsmanship reflect a rich tapestry of ancient wisdom, seamlessly blending martial prowess with profound spiritual and ethical principles. This unique fusion has shaped the art of Chinese swordsmanship into a discipline that transcends mere combat, becoming a path for personal cultivation and enlightenment.

Daoist influence on swordsmanship emphasizes harmony, balance, and fluidity in combat techniques. The concept of “wu-wei” or effortless action is particularly evident in the Wudang Sword style, which originated from the sacred Wudang Mountains. Practitioners strive to achieve a state of natural flow, where their movements become an extension of the universe’s inherent rhythms. This approach encourages swordsmen to adapt to changing situations with grace and efficiency, mirroring the Daoist principle of aligning oneself with the Dao or the natural way of things.

Confucian principles have also left an indelible mark on Chinese swordsmanship, introducing the ideal of the “gentleman of weapons.” This concept emphasizes moral discipline and ethical conduct in swordsmanship, elevating the practice beyond mere martial skill. Sima Qian, the great historian, articulated that those engaged in “military affairs and sword discourse” must possess the four virtues of faith, integrity, benevolence, and courage. This Confucian influence transformed swordsmanship into a means of cultivating one’s character, with the sword becoming a tool for moral and ethical refinement.

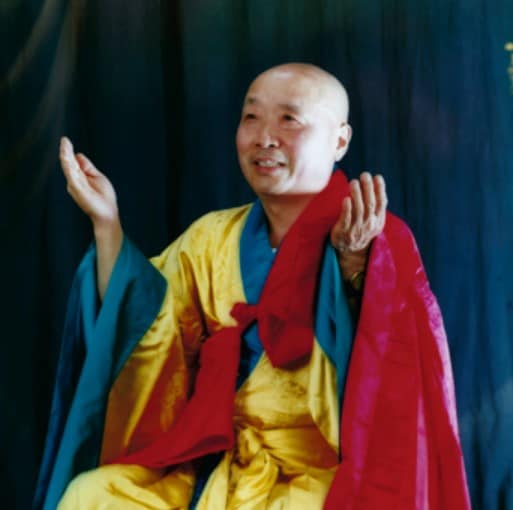

The integration of Buddhist concepts into Chinese swordsmanship brought a focus on mind-body cultivation through meditative practices. This is particularly evident in styles like Shim Gum Do, introduced by a South Korean Buddhist monk. These practices aim to unify the practitioner’s inner mind with their physical movements, creating a state of heightened awareness and presence. The goal is to achieve a state where the sword and the wielder become one, transcending the duality of self and action.

Here’s a table summarizing the key philosophical influences on Chinese swordsmanship:

| Philosophy | Key Concept | Impact on Swordsmanship |

| Daoism | Wu-wei (effortless action) | Fluid, adaptive techniques |

| Confucianism | Moral cultivation | Ethical conduct in martial arts |

| Buddhism | Mind-body unity | Meditative sword practices |

Chinese swordsmanship, with its deep philosophical underpinnings, offers more than just martial techniques. It provides a holistic approach to personal development, combining physical skill with spiritual growth and ethical refinement.

Legendary Swords and Their Philosophical Significance

The legendary swords of Chinese history are not merely weapons; they are embodiments of profound philosophical concepts that have shaped Chinese culture for millennia. These blades, steeped in myth and legend, carry with them stories of heroism, sacrifice, and wisdom that continue to resonate in modern times.

Gan Jiang and Mo Ye, a pair of swords named after their creators, represent a powerful metaphor for unity, sacrifice, and duality in Daoist thought. According to legend, the swordsmith Gan Jiang and his wife Mo Ye labored tirelessly to forge these blades for the King of Wu. When the furnace failed to reach the necessary temperature, Gan Jiang sacrificed himself by jumping into the flames, while Mo Ye followed suit, their combined essence imbuing the swords with extraordinary power. This tale reflects the Daoist concept of yin and yang, the complementary forces that create harmony in the universe. The swords symbolize the union of masculine and feminine energies, and the sacrifice required to achieve true balance.

The Sword of Goujian, a marvel of ancient Chinese metallurgy, embodies the virtues of resilience and strategic patience. Discovered in 1965 in an archaeological dig, this 2,500-year-old blade was found to be in remarkably pristine condition, still sharp enough to cut through paper. The sword belonged to King Goujian of Yue, who ruled during the tumultuous Spring and Autumn Period (771-476 BCE). Goujian’s story of perseverance – enduring years of humiliation as a captive before ultimately defeating his rivals – is reflected in the sword’s enduring quality. This blade serves as a tangible reminder of the Confucian virtues of patience and self-cultivation in the face of adversity.

The Green Dragon Crescent Blade, associated with the legendary general Guan Yu, stands as a symbol of loyalty and righteousness. Although its historical existence is debated, with some scholars suggesting it may not have been used until centuries after Guan Yu’s time, its legendary status is undeniable. In the classic novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” this massive guandao is described as a weapon of immense power, wielded by Guan Yu with supernatural skill. The blade’s association with Guan Yu, who is revered as a god of war and symbol of brotherhood, imbues it with the Confucian ideals of loyalty to one’s allies and unwavering moral integrity.

These legendary Chinese swords and their philosophical significance can be summarized as follows:

| Sword | Philosophical Concept | Historical/Legendary Context |

| Gan Jiang and Mo Ye | Unity, sacrifice, duality | Daoist yin-yang balance |

| Sword of Goujian | Resilience, strategic patience | Spring and Autumn Period |

| Green Dragon Crescent Blade | Loyalty, righteousness | Three Kingdoms era |

Schools of Swordsmanship and Philosophical Teachings

The schools of Chinese swordsmanship and their philosophical teachings represent a rich tapestry of martial arts traditions that evolved over centuries, reaching a particularly notable period of development during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). These schools not only focused on martial techniques but also integrated profound philosophical concepts, creating a holistic approach to swordsmanship that went beyond mere combat.

Internal styles, known as Neijia (內家), gained prominence during the Ming Dynasty, emphasizing subtlety, balance, and a non-reliance on physical strength. These styles focused on cultivating internal energy, or qi, and applying it in combat. Neijia practitioners believed that true mastery came from within, developing a deep mind-body connection that allowed for effortless and efficient movement. The concept of “wu-wei” or effortless action, derived from Daoist philosophy, was particularly influential in these internal sword styles.

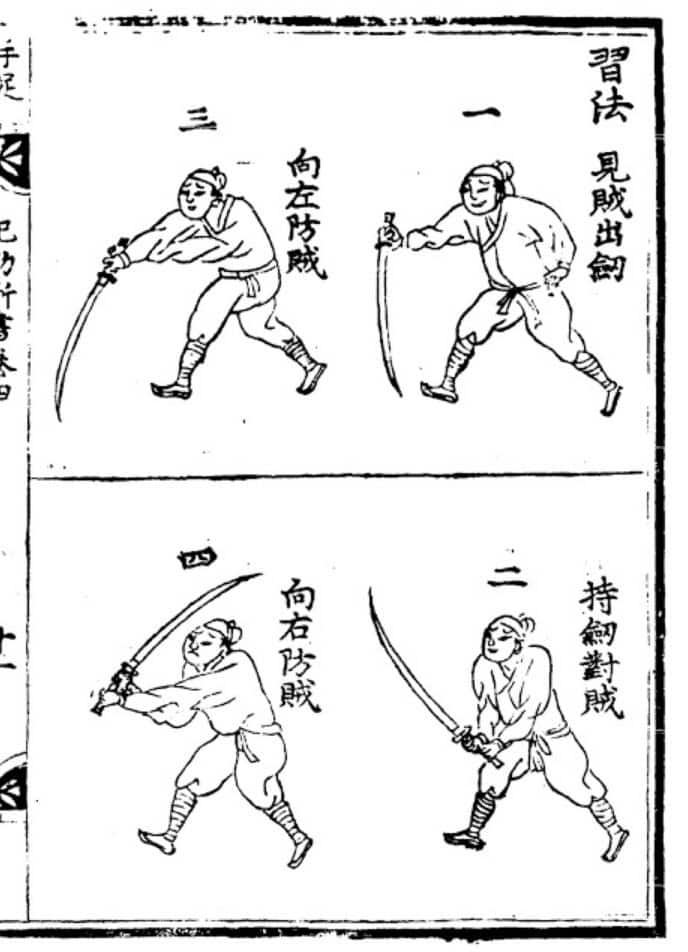

During the Ming Dynasty, five or six major civilian fencing schools emerged, each emphasizing erudition and philosophical depth alongside martial skill. These schools moved away from purely militaristic approaches, integrating scholarly pursuits and ethical considerations into their teachings. One notable example is the system described in the “Dan Dao Fa Xuan” (單刀法選) by Cheng Zong You (程宗猷), which refined techniques for the Chang Dao (長刀) or long saber. These civilian schools often drew inspiration from classical Chinese philosophy, incorporating elements of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism into their teachings.

The integration of martial arts with regional philosophies and techniques led to the development of unique schools across China. This blending of philosophy with technique resulted in diverse approaches to swordsmanship, each reflecting the cultural and philosophical nuances of its region. For instance, the Wudang sword style, associated with Daoist monasteries in the Wudang Mountains, became renowned for its emphasis on circular movements and internal energy cultivation.

Here’s a table summarizing some key aspects of Chinese swordsmanship schools during the Ming Dynasty:

| School Type | Key Characteristics | Philosophical Influence |

| Internal (Neijia) | Subtlety, balance, qi cultivation | Daoism, Buddhism |

| Civilian Fencing | Scholarly approach, ethical considerations | Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism |

| Regional Styles | Unique techniques blended with local philosophies | Varied (Daoism, Buddhism, folk beliefs) |

The evolution of these schools of Chinese swordsmanship fascinates me on a personal level. I find the idea of martial arts as a path to self-cultivation and philosophical enlightenment particularly compelling. The way these ancient masters integrated deep philosophical concepts into practical combat techniques speaks to a holistic approach to personal development that I believe has relevance even in our modern world.

Final Thoughts

As I reflect on Chinese sword philosophy, I’m struck by how relevant these ancient ideas still are today. The balance of Daoist thought, the moral righteousness of Confucianism, and the mind-body harmony of Buddhism – all embodied in the art of the sword – offer timeless lessons. While I may never wield a Jian like the legendary swordsmen of old, I find myself applying these philosophical principles in my daily life.