From Stone Age to Steel: The History of Hammers

The history of hammers is a journey through time, revealing the ingenuity of humanity and the vital role that tools have played in our evolution. Hammers, simple yet versatile instruments, have been used for millennia to shape our world, from building structures to crafting intricate works of art. This exploration will take us from the earliest known hammer-like tools to the modern variations we use today, showcasing the enduring impact of this fundamental invention.

Definition of a Hammer

A hammer is a versatile hand tool, featuring a weighted “head” securely attached to a long handle. It is designed to deliver precise impacts to a targeted area of an object, serving a multitude of purposes.

Hammers are commonly used to drive nails into wood, shape metal at a forge, or even crush rocks. This indispensable tool finds its applications in carpentry, blacksmithing, warfare, and even percussive music, such as striking a gong.

The act of hammering involves using a hammer in its striking capacity, as opposed to prying or grappling. Carpentry and blacksmithing hammers are typically wielded with one arm in a stationary stance, delivering a downward planar arc with a brisk wrist rotation before impact.

In contrast, war hammers are employed with a broader range of motion, often incorporating the legs and hips and allowing for a lunging motion, especially against moving targets. Smaller mallets can be swung from the wrists, enabling a higher cadence of repeated strikes.

Modern hammerheads are typically constructed from heat-treated steel for hardness, while the handle, known as a haft or helve, is commonly made from wood or plastic. Among the various types of hammers, the claw hammer stands out, featuring a claw for removing nails, making it a staple in North American households. Sledgehammers, mallets, and ball-peen hammers are among the other specialized types, each designed with a specific purpose in mind.

Though most hammers are hand tools, powered versions like steam hammers and trip hammers are employed when dealing with forces beyond human capacity. With over 40 different types of hammers tailored for various applications, these tools continue to be indispensable across industries.

The grip of the shaft is another crucial consideration. To ensure safety and control during heavy work, modern hammers with steel shafts are often coated with synthetic polymers, enhancing grip, dampening vibrations, and providing thermal insulation. The handle’s contour also plays a significant role in maintaining a secure grip during intense usage. While traditional wooden handles are serviceable, steel handles offer superior strength and durability, albeit with safety concerns if the head becomes loose on the shaft.

What’s the History of Hammers?

Simple hammers trace their origins back to approximately 3.3 million years ago, as evidenced by a remarkable discovery in 2012. Sonia Harmand and Jason Lewis of Stony Brook University uncovered a substantial deposit of stones with various shapes near Kenya’s Lake Turkana. These stones were employed to strike wood, bone, or other stones to break and shape them, signifying the early use of hammers in human history.

In their earliest form, hammers were devoid of handles. Instead, stones were affixed to sticks using strips of leather or animal sinew. This ingenious adaptation allowed for more precise control and reduced the risk of accidents.

This transition, occurring around 30,000 BCE during the middle of the Paleolithic Stone Age, marked a pivotal moment in hammer evolution. With the addition of handles, hammers became indispensable tools for a wide range of applications, including construction, food preparation, and personal protection.

The archaeological record suggests that the hammer may well be one of the oldest tools for which we possess definitive evidence.

Construction and Hammer Variations

A traditional hand-held hammer typically consists of two main components: the head and the handle. These parts can be securely fastened together using a special wedge designed for this purpose or through the use of glue, or sometimes both methods are combined.

This two-piece design often pairs a dense metallic striking head with a non-metallic handle, which serves to absorb mechanical shock, reducing user fatigue caused by repeated strikes.

Common materials for hammer handles include hickory or ash wood, known for their durability and shock-absorbing properties. Alternatively, rigid fiberglass resin can be used for handles, offering resistance to water absorption and decay, though it doesn’t dissipate shock as effectively as wood.

To prevent the dangerous situation of a loose hammer head becoming detached during a swing, safety measures are crucial. Wooden handles, when worn or damaged, can often be replaced using specialized kits that cover various handle sizes and designs. These kits may also include wedges and spacers for secure attachment.

Some hammers deviate from the two-piece design and are crafted as one-piece tools, primarily from a single material. In such cases, the handle may be coated or wrapped in a resilient material like rubber to enhance grip and reduce user fatigue.

The head of a hammer can be surfaced with various materials, including brass, bronze, wood, plastic, rubber, or leather. Additionally, certain hammers feature interchangeable striking surfaces, allowing users to select the most suitable surface for their specific task or to replace it when it wears out.

Variations

Hammers come in a multitude of designs and variations, each tailored to specific applications and industries. Here are some noteworthy examples:

- Maul: A large hammer-like tool, often used for heavy-duty tasks, such as driving wedges or splitting wood.

- Mallet: Typically featuring a wooden or rubber head, mallets are used for tasks where a softer impact is required, such as woodworking or upholstery.

- Hatchet: A hammer-like tool equipped with a cutting blade, commonly used for cutting and chopping tasks.

- Ball-Peen Hammer: This hammer has a flat striking surface on one end and a rounded ball-shaped end on the other, making it suitable for various metalworking tasks.

- Demolition Hammer: Designed for heavy-duty demolition work, these hammers are built to withstand intense use.

- Geologist’s Hammer: Specifically crafted for geological and rock-related tasks, featuring a pick-like end for breaking rocks.

- Sledgehammer: Known for its sheer force, sledgehammers are heavy-duty hammers used for breaking, shaping, or driving tasks.

- Soft-Faced Hammer: Equipped with non-metallic striking surfaces, these hammers are ideal for tasks where marring or damage to the material is a concern.

- Upholstery Hammer: Some upholstery hammers feature a magnetized face for picking up tacks, making them ideal for upholstery work.

- Welder’s Chipping Hammer: Designed for removing slag and debris from welds, ensuring clean and smooth weld surfaces.

- Railway Track Keying Hammer: Specialized hammers used in railway maintenance and repair.

- Lathe Hammer: Combines a small hatchet blade with a hammer head, used for cutting and nailing wood lath.

- Tinner’s Hammer: Used in sheet metal work, with one flat face and one pointed face for various tasks.

War Hammers

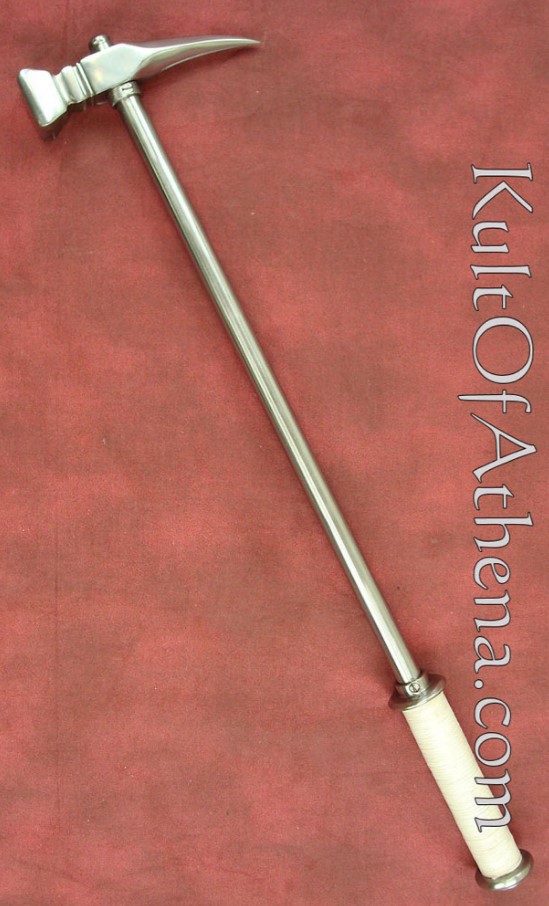

A war hammer, also known as a martel-de-fer (French for “iron hammer”), is a historic weapon with a rich legacy in both infantry and cavalry combat. This formidable weapon earned its name from its widespread use and association with notable figures like Judah Maccabee and Charles Martel.

Historical Significance

The war hammer has ancient origins, dating back to the 2nd century BC when it was employed by Jewish rebel Judah Maccabee and later gained recognition through the exploits of Charles Martel, a French ruler. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the war hammer evolved from a functional weapon into an elaborately decorated and aesthetically pleasing instrument of war.

Design

A war hammer is composed of two primary components: a handle and a head. The length of the handle varied, with long war hammers akin to halberds (ranging from five to six feet or 1.5 to 1.8 meters) and shorter versions resembling maces (measuring two to three feet or 60 to 90 centimeters).

Long war hammers were typically used on foot, while shorter ones were wielded from horseback. The head of a war hammer was its defining feature. It could deliver powerful blows due to its heavy impact without needing to pierce the opponent’s armor.

Some war hammers featured a spike on one side of the head, enhancing their versatility. The spike could be used for grappling the target’s armor, reins, or shield. When facing mounted opponents, it could be directed at the horse’s legs, toppling the armored foe to the ground, where they became vulnerable.

The primary tactic employed with a war hammer was to stun the enemy with the flat side of the head, followed by reversing it to punch a hole through the opponent’s helmet to deliver the finishing blow. The sheer force of a war hammer swing could generate impact forces equivalent to several hundred kilograms per square millimeter, akin to a rifle bullet’s penetrating force.

Maul

A related weapon to the war hammer is the maul, characterized by its long handle and a heavy head made of materials such as wood, lead, or iron. It bears a resemblance to a modern sledgehammer and sometimes features a spear-like spike on the fore-end of the haft.

The use of the maul as a weapon can be traced back to the late 14th century, as seen during events like the Harelle of 1382 when rebellious citizens of Paris seized thousands of mauls from the city armory.

Archers in the 15th and 16th centuries notably used lead mauls. At the Battle of Agincourt, English longbowmen employed them as both tools to drive stakes and improvised weapons. References from this period indicate the continued use of mauls as weapons.

Conclusion

The history of hammers demonstrates human innovation and adaptability. From the humble beginnings of stone and wood implements to the diverse range of specialized hammers we have today, these tools have remained essential in our quest to build, create, and shape the world around us.

As we continue to refine and develop new hammer designs, we honor the legacy of countless generations who have relied on this remarkable tool to forge a better future. Hammers, in their simplicity, continue to be a symbol of human progress and our unwavering determination to shape our world.