Sword Duel Chronicles: Reliving the Fiercest Fights of Old

Ah, the age-old clash of steel, where honor, pride, and the gleam of a well-sharpened blade collide in a dance of deadly elegance. Picture this: two valiant warriors, faces etched with determination, swords glinting in the sunlight, poised for a duel that will determine fates and destinies.

If you’ve ever watched your fair share of movies or TV shows, you know that sword duels are the stuff of legends – those epic confrontations that leave us on the edge of our seats, with bated breath, and maybe even unconsciously attempting some swashbuckling moves in the living room.

From the dramatic face-offs of medieval knights to the flashy displays of finesse in historical dramas, the art of sword dueling has captured our imaginations for centuries. Think about it: Tyrion Lannister’s clever wit combined with Bronn’s skill in “Game of Thrones,” Inigo Montoya’s unforgettable quest for vengeance in “The Princess Bride,” and who could forget the dazzling choreography of Obi-Wan Kenobi and Darth Maul in “Star Wars”?

In this journey into the world of sword duels, we’re slicing through history and fiction, diving into the heart-pounding clashes that have enthralled us on screen and echoed through time. Let’s sharpen our mental blades, suit up in our virtual armor, and venture into a realm where honor meets steel in the most riveting and cinematic way possible.

What is a Sword Duel?

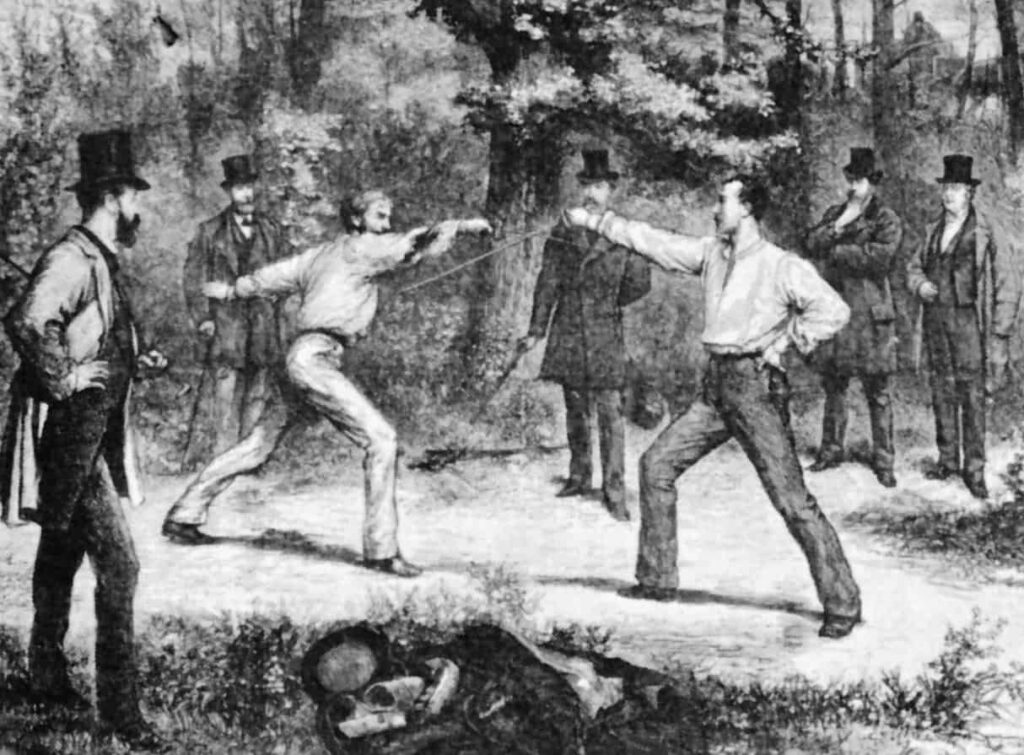

Dueling, a formal combat arrangement between two individuals, originated during medieval times and persisted into the 17th to 19th centuries. It involved participants engaging in combat using agreed-upon rules and weapons of equal choice. The primary motivation behind dueling was to uphold one’s honor rather than necessarily causing harm to the opponent.

The practice of dueling can be traced through various historical phases:

- Early History and Middle Ages: Dueling evolved from medieval judicial combat and other pre-Christian customs like the Viking Age holmgang. Judicial duels, intended to settle disputes, took on forms such as the “feat of arms” and “chivalric combat.” A duel concluded when one party could no longer continue, though criticism of this practice arose from the Catholic Church.

- Renaissance and Early Modern Europe: The Renaissance period saw dueling gain recognition as an acceptable method for gentlemen to resolve conflicts. Despite efforts to suppress it, dueling remained popular in European societies. National codes of dueling were introduced during this era, with France’s being noteworthy.

- Enlightenment-Era Opposition: As the 18th century advanced, Enlightenment ideals advocating politeness and condemning violence began challenging the legitimacy of dueling. Urbanization and enhanced law enforcement reduced street violence. Intellectual shifts and social activism further fueled anti-dueling sentiments.

- Modern History: Despite facing resistance, dueling persisted into the 19th century, resulting in the deaths of prominent figures like Alexander Hamilton. During the early 19th century, pistols gained preference over swords in English duels. The decline of dueling was marked by legal changes and shifting societal attitudes.

Throughout its existence, dueling was tightly connected to honor, chivalry, and social standing. Although initially favored by the aristocracy and elite, dueling waned as societal norms evolved, laws tightened, and perceptions of violence and honor transformed. By the mid-19th century, dueling had largely lost favor across Europe and the United States.

Sword Duel Etiquette and Rules

Dueling was governed by a set of rules and protocols that were closely tied to notions of honor and respect. The practice typically arose following a perceived offense, whether real or imagined. When one party felt slighted, they would demand “satisfaction” from the offender, often signaled by a deliberately insulting gesture such as throwing a glove.

Challenges were usually delivered in written form by trusted friends acting as “seconds.” These challenges outlined the grievances and the demand for satisfaction, with formal language. The challenged party had the option to accept or decline the challenge.

Declining a challenge, however, could lead to accusations of cowardice or insults toward the seconds. The choice of weapons for the duel was usually made by the challenged party. If the challenge was accepted, both parties would appoint seconds to handle the arrangements.

The role of seconds was crucial in averting bloodshed if possible. They would attempt to find a mutually agreeable resolution that could include a formal apology. If a peaceful resolution failed, the seconds would negotiate terms for the duel.

The specifics of dueling etiquette varied across time and regions, often referred to as the “code duello.” Sword duels were popular in parts of Europe, while pistols were favored in the United States and Great Britain.

The duration and conditions of the duel were established beforehand by the seconds. Sword duels might only continue until blood was drawn to limit fatalities. Pistol duels specified the number of shots and the range.

The chosen ground was meticulously selected to avoid providing an advantage to either party. Arrangements were made for medical assistance, and even finer details like dress code and witnesses were settled.

Dueling locations were chosen for isolation and jurisdictional ambiguity to avoid legal consequences. Duels often took place at dawn, ensuring poor visibility and allowing time for second thoughts. Before the mid-18th century, participants in dawn sword duels carried lanterns to see each other, influencing fencing techniques.

Duels could conclude in several ways:

- To First Blood: The duel ended when one participant was wounded, even if the wound was minor.

- Until Physically Unable: The duel continued until one participant was too injured to continue.

- To the Death: No satisfaction was achieved until one participant was mortally wounded.

- Pistol Duels: Each party fired one shot, and if no one was hit and the challenger was satisfied, the duel ended. Otherwise, the duel continued until a hit was achieved or one participant was wounded or killed.

Practices could vary. Deliberate misses, known as “deloping,” were sometimes used to fulfill the conditions without causing harm. However, this was generally seen as dishonorable. The challenged party usually had the authority to stop the duel if they considered their honor satisfied. In some cases, if the primary duelist was unable to continue, the seconds would step in.

Famous Sword Duels in History

Évariste Galois

Évariste Galois, a remarkable French mathematician and passionate political activist, is remembered not only for his groundbreaking contributions to abstract algebra but also for a tragic and fatal duel.

Galois, born on October 25, 1811, demonstrated exceptional mathematical prowess during his teenage years, formulating crucial concepts in algebra that would pave the way for Galois theory and group theory.

He was deeply engaged in the tumultuous political climate surrounding the French Revolution of 1830, which led to his repeated arrests and imprisonment due to his strong republican views.

After his expulsion from École Normale, Galois persisted in both mathematics and political activities. He sought to establish an advanced algebra class but encountered challenges due to his prioritization of political endeavors.

He submitted his work on the theory of equations to Siméon Denis Poisson, a renowned mathematician, which was met with a response of incomprehensibility. Despite this setback, Galois continued refining his ideas in prison and was encouraged to publish his work to form a comprehensive judgment.

It was during his tumultuous time in prison that the events leading to the fatal duel unfolded. For reasons that remain unclear, shortly after his release from prison in April 1832, Galois found himself embroiled in a duel. On May 30, 1832, the duel took place, resulting in Galois’s tragic demise. The precise motivations behind this duel remain shrouded in mystery and speculation.

In the days leading up to the duel, Galois had written a letter to his friend Auguste Chevalier, indicating a broken romantic relationship. There is evidence suggesting that Galois was romantically involved with Stéphanie-Félicie Poterin du Motel, the daughter of the physician where he resided. Galois’s letters hint at his involvement in her personal troubles and his decision to provoke the duel on her behalf.

While Alexandre Dumas named Alexandre Dumas names Pescheux d’Herbinville as Galois’s opponent in the duel, this assertion remains contested, with historical details pointing to other possibilities, including Ernest Duchatelet, a Republican friend of Galois who shared his imprisonment.

Regardless of the true identity of his opponent, Galois’s conviction of his impending death prompted him to write letters to his friends and compose a mathematical testament.

In this testament, he outlined his mathematical ideas and left behind profound contributions to the field of mathematics. Galois’s legacy continues to live on through his work and the tragic circumstances that surrounded his life and death.

Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojiro

The historical duel between Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojirō is a renowned episode in Japanese history that showcases the clash of two exceptional swordsmen and their contrasting styles.

Miyamoto Musashi, recognized as a legendary swordsman, philosopher, and strategist, initiated the duel with Sasaki Kojirō, a skilled swordsman known for his unique fighting techniques and formidable “laundry-drying pole” nodachi.

Scheduled for April 13, 1612, the duel took place on the island of Ganryūjima, a location between Honshū and Kyūshū. Musashi, approximately 30 years old at the time, arrived late for the confrontation, a gesture that some accounts suggest was intentional to display disrespect.

Kojirō, renowned for his swift two-stroke sword technique called “tsubame gaeshi,” or “swallow reversal,” awaited his opponent with impatience and frustration, even discarding his scabbard as a declaration of his intent to fight to the death.

As the duel commenced, the two combatants circled each other with anticipation. Kojirō, known for his overhead strike, lunged forward with his trademark move. Musashi responded with a leap and a powerful swing of his weapon, resulting in a dramatic clash of their swords.

In a moment of intense intensity, Musashi’s headband was cut, but miraculously, his skull remained unscathed. In contrast, Musashi’s strike found its mark, slicing through Kojirō’s skull.

The duel’s outcome solidified Musashi’s victory, but it also immortalized Sasaki Kojirō as a respected and revered warrior in Japanese culture. Despite the defeat and his tragic end, Kojirō’s legacy endures as an example to his skill and valor.

The duel between these two remarkable swordsmen remains an iconic event that continues to captivate the imagination of those intrigued by Japan’s rich history and martial traditions.

The Most Iconic Duels in Pop Culture

As for the most memorable sword duels in pop culture? Well, there are just too many to count. Check out this video by Watch Mojo and see if you agree with their list!

Conclusion

In the world of combat and chivalry, few spectacles command the same level of awe and fascination as the classic sword duel. Our journey through the sword duel history has whisked us away to a time when honor and valor were often measured in the clash of steel, and the outcome of a duel could change the course of history.

As we conclude this exploration into the fiercest fights of old, we find ourselves immersed in the echoes of a bygone era, where warriors stood tall, faces masked with determination, and hearts afire with a thirst for victory.