Han Xin

TLDR: Han Xin, a brilliant general of the Han Dynasty, rose from humble beginnings to lead key military campaigns, but faced execution in 196 BCE amid political strife.

Han Xin, a name that sends shivers down my spine every time I hear it. This military genius of ancient China, who lived from 231 to 196 BCE, was the architect behind some of the most brilliant strategies in warfare history. From his humble beginnings to becoming the general-in-chief of Liu Bang’s forces, Han Xin’s life reads like an epic saga of triumph and tragedy. His tactical innovations, like the “Chencang Road” strategy, and his pivotal role in the Chu-Han Contention, showcase a mind that was light-years ahead of its time. I can’t help but marvel at how one man’s intellect shaped the course of an entire dynasty.

Early Life of Han Xin

Han Xin was born in Huaiyin, located in modern-day Jiangsu Province, during the tumultuous period of the late Qin dynasty. His exact birth year is unknown, but it is estimated to be around 231 BCE. Han Xin’s family background is a subject of some debate among historians. While some sources suggest he may have been a descendant of the Han Sect of the Han Kingdom, his early life was marked by extreme poverty. This contradiction between potential noble lineage and impoverished circumstances adds an intriguing layer to Han Xin’s origin story.

Han Xin’s youth was fraught with hardship and adversity. The loss of his father at a young age left him in dire straits, often struggling to secure his next meal. This period of destitution shaped Han Xin’s character profoundly, instilling in him a resilience that would serve him well in his later military career.

One of the most formative experiences of Han Xin’s early life was his encounter with an old woman by the river. For several days, this woman provided him with food while she did her laundry. Han Xin’s promise to repay her kindness was met with a stern rebuke, teaching him a valuable lesson about genuine altruism.

Another pivotal moment in Han Xin’s youth was his confrontation with a local hooligan. Challenged to either stab the man or crawl between his legs, Han Xin chose the path of humiliation over violence. This decision, while mocked by his peers at the time, demonstrated Han Xin’s ability to endure short-term humiliation for long-term gain – a trait that would prove crucial in his future military strategies.

Despite these challenges, Han Xin devoted himself to self-improvement. He spent his time studying “The Art of War” and practicing martial arts, laying the foundation for his future military expertise.

Han Xin’s Rise to Military Leadership

Han Xin’s journey to military leadership began when he defected from Xiang Yu’s camp and joined Liu Bang’s forces around 206 BCE. Initially, Han Xin held no significant position in Liu Bang’s army and was even at risk of execution for violating military law. However, his potential was recognized by Xiahou Ying, one of Liu Bang’s trusted generals, who spared Han Xin’s life after being impressed by his words and demeanor.

Despite this reprieve, Han Xin’s talents were not immediately utilized. Liu Bang appointed him as Captain of Rations (治粟都尉), a role that primarily involved managing food supplies. During this time, Han Xin frequently met with Xiao He, Liu Bang’s Chancellor, who recognized his exceptional abilities.

Han Xin’s ascent to the highest military rank was largely due to Xiao He’s persistent advocacy. In a dramatic turn of events, Xiao He pursued Han Xin throughout the night when he learned of Han Xin’s intention to leave Liu Bang’s service. This incident, known as “Xiao He pursuing Han Xin under the moon,” became legendary.

Upon Xiao He’s insistence, Liu Bang reluctantly agreed to promote Han Xin to the position of Commander-in-Chief (大將軍). Xiao He emphasized the need for a formal ceremony to mark this significant appointment, which Liu Bang eventually conceded to hold.

Han Xin’s “Chencang Road” strategy, known as “mingxiu zhandao, andu Chencang” (明修棧道, 暗度陳倉), exemplifies his tactical brilliance. This strategy, employed during the conquest of the Three Qins in late 206 BCE, involved a clever deception. Han Xin ordered some troops to openly repair gallery roads linking Guanzhong and Hanzhong, creating a diversion. Simultaneously, he secretly dispatched another force through Chencang to launch a surprise attack on Zhang Han. This maneuver caught the enemy off guard, leading to a decisive victory for Han forces.

Han Xin was a master of psychological warfare, often manipulating enemy perceptions to gain an advantage. One notable example is his strategy at the Battle of Jingxing. Han Xin positioned a small force with their backs to a river, appearing to leave no retreat option. This bold move instilled overconfidence in the opposing Zhao army, leading them to underestimate Han Xin’s true strength. Additionally, Han Xin used flags and musical instruments to create an illusion of a larger force, further manipulating enemy perceptions.

Han Xin’s genius in utilizing terrain and positioning is evident in many of his campaigns. At the Battle of Jingxing, he expertly used the mountainous terrain to his advantage. By sending a small cavalry force along a goat track to position themselves behind the enemy camp, Han Xin created a multi-pronged attack that overwhelmed the Zhao forces. His ability to assess and exploit geographical features often allowed him to overcome numerically superior enemies.

Han Xin’s Major Campaigns

Han Xin’s conquest of the Three Qins in late 206 BCE marked the beginning of his illustrious military career. Employing his famous “Chencang Road” strategy, Han Xin ordered troops to openly repair gallery roads linking Guanzhong and Hanzhong as a diversion, while secretly dispatching forces through Chencang to launch a surprise attack on Zhang Han. This clever maneuver caught the enemy off guard, leading to a swift victory. Han Xin’s forces quickly overran Guanzhong within a month, demonstrating his tactical brilliance and the effectiveness of his deception strategies.

Following the success in Guanzhong, Han Xin launched a rapid northern campaign against the kingdoms of Wei, Dai, and Zhao between August and October 205 BCE. His swift and unexpected movements caught these states by surprise, leading to their quick collapse. Han Xin’s ability to capture the kings of Wei, Dai, and Zhao in rapid succession showcased his strategic acumen and the speed of his military operations. This campaign was crucial in securing the northern territories for Liu Bang’s Han faction.

The Battle of Jingxing in October 205 BCE stands as one of Han Xin’s most brilliant tactical victories. Facing a numerically superior Zhao army led by Chen Yu, Han Xin positioned his troops with their backs to the Mienman River, leaving no retreat option. This bold move, combined with his clever use of terrain and psychological warfare, led to a decisive victory. Han Xin sent 2,000 light cavalry to seize the Zhao camp from behind, causing panic in the enemy ranks. The resulting chaos allowed Han Xin to launch a devastating counterattack, resulting in the complete defeat of the Zhao forces.

Han Xin’s invasion of Qi in October 204 BCE demonstrated his political astuteness and military prowess. Despite learning that Liu Bang had sent a diplomat to negotiate with Qi, Han Xin proceeded with the invasion on the advice of his counselor, Kuai Tong. He swiftly defeated the Qi army at Lixia and captured the capital, Linzi. This campaign not only secured the rich and populous state of Qi for the Han faction but also positioned Han Xin to potentially invade the Chu heartland, further pressuring Xiang Yu.

| Campaign | Date | Key Strategy | Outcome |

| Three Qins Conquest | Late 206 BCE | Chencang Road deception | Swift victory in Guanzhong |

| Northern Campaign | Aug-Oct 205 BCE | Rapid, successive invasions | Capture of Wei, Dai, and Zhao |

| Battle of Jingxing | October 205 BCE | River-backed positioning, surprise attack | Decisive defeat of Zhao army |

| Invasion of Qi | October 204 BCE | Swift strike despite diplomatic efforts | Capture of Linzi, control of Qi |

Han Xin’s Role in the Chu-Han Contention

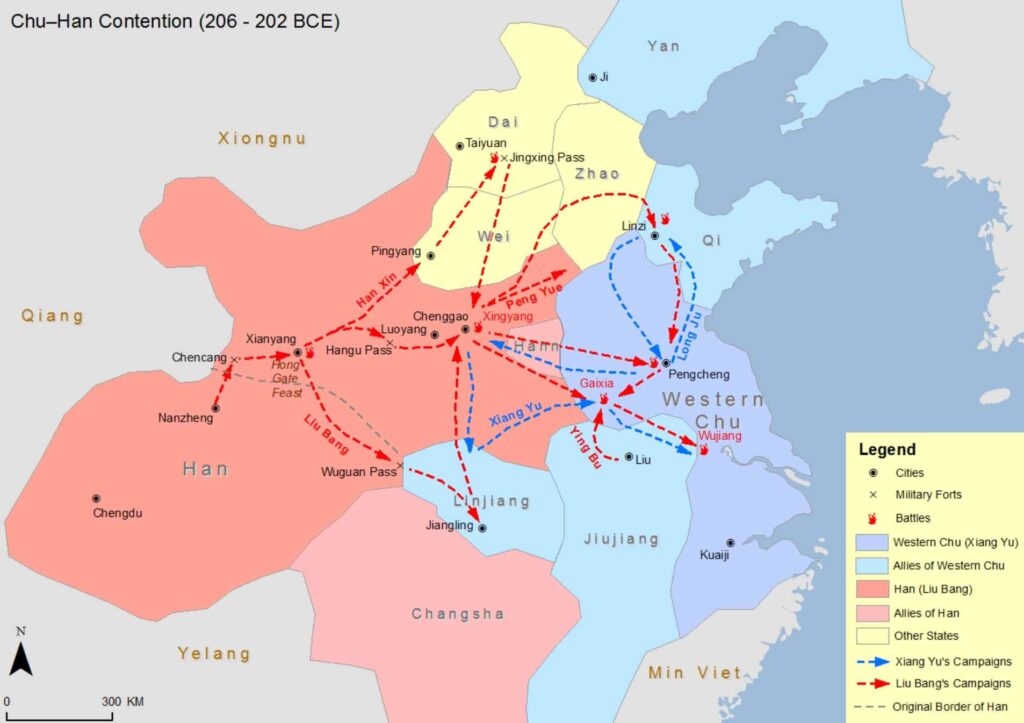

Han Xin played a pivotal role in shaping the overall strategy for Liu Bang during the Chu-Han Contention. As the general-in-chief, he devised a two-front war strategy that proved crucial to the Han faction’s success. This plan involved Liu Bang stalling Xiang Yu in the Central Plains while Han Xin focused on conquering the northern vassal states. By securing Guanzhong early in the conflict, Han Xin established an ideal defensive and offensive center of operations, leveraging its abundant agriculture, large population, and natural defensibility.

Han Xin’s strategic brilliance was evident in his decision to avoid direct combat with the formidable Xiang Yu until the final months of the war. Instead, he systematically stripped Chu of its crucial northern vassals: Wei, Dai, Zhao, Yan, and Qi. This approach secured a massive superiority in food and manpower for the Han faction, significantly weakening Chu’s position.

Han Xin’s ability to coordinate complex, multi-pronged attacks was a key factor in the Han victory. The Gaixia campaign of 203-202 BCE exemplifies this skill, as Han Xin orchestrated a simultaneous invasion from multiple directions. Forces under his command attacked from the north-east, while other Han armies advanced from the north-west (led by Peng Yue), central-west (Liu Bang), south-west (Ying Bu), and south (Zhou Yin and Liu Jia).

This coordinated assault demonstrated Han Xin’s exceptional ability to manage large-scale military operations across vast distances. His strategic planning ensured that these diverse forces could rendezvous effectively at Gaixia, overwhelming Xiang Yu’s defenses.

The Gaixia campaign marked the culmination of Han Xin’s military genius in the Chu-Han Contention. At Gaixia, Han Xin employed tactics reminiscent of Hannibal’s strategy at Cannae. He formed two reserve lines and advanced his center against Xiang Yu’s forces. When the center failed to gain an advantage, Han Xin withdrew it, likely luring Xiang Yu’s men into pursuit. Han Xin then executed a double envelopment, with his left and right flanks attacking Xiang Yu’s army from both sides.

Han Xin’s tactical acumen was further demonstrated by his use of psychological warfare. He ordered his troops to sing Chu folk songs, demoralizing Xiang Yu’s soldiers by reminding them of their distant homes and families6. This “Chu Song Stratagem” caused many of Xiang Yu’s troops to desert or lose their fighting spirit, contributing significantly to the Han victory.

| Aspect | Description | Impact |

| Strategic Planning | Two-front war strategy | Weakened Chu by stripping northern vassals |

| Multi-Pronged Attacks | Coordinated invasions from multiple directions | Overwhelmed Xiang Yu’s defenses at Gaixia |

| Tactical Brilliance | Double envelopment at Gaixia | Decisive victory in the final battle |

| Psychological Warfare | “Chu Song Stratagem” | Demoralized enemy troops, causing desertions |

Han Xin’s Contributions to the Han Dynasty

Han Xin played a crucial role in the territorial expansion of the Han Dynasty, significantly enlarging its borders and consolidating its power. His military campaigns were instrumental in conquering the Three Qins in Guanzhong, which provided the Han with a strategic base of operations. This conquest was achieved through Han Xin’s innovative “Chencang Road” strategy, demonstrating his ability to combine deception with military might.

Han Xin’s subsequent northern campaigns against Wei, Dai, and Zhao in 205 BCE further expanded Han territory. His swift and decisive actions led to the capture of these kingdoms’ rulers, effectively bringing vast northern regions under Han control. These conquests not only expanded the Han Dynasty’s territorial reach but also secured valuable resources and manpower that would prove crucial in the ongoing struggle against Xiang Yu’s Chu forces.

Han Xin’s contributions to the Han Dynasty extended beyond territorial gains to include significant military reforms and innovations. His tactical brilliance reshaped Han military strategy, introducing new approaches to warfare that would influence Chinese military thought for centuries to come.

One of Han Xin’s most notable innovations was his use of psychological warfare. At the Battle of Jingxing, he employed tactics such as positioning troops with their backs to a river and using flags and musical instruments to create the illusion of a larger force. These psychological tactics, combined with his strategic use of terrain, allowed Han Xin to overcome numerically superior enemies.

Han Xin also introduced reforms in military organization and training. While specific details of these reforms are not provided in the search results, his emphasis on speed, coordination, and adaptability in military operations suggests that he likely implemented changes to improve the mobility and responsiveness of Han forces.

| Contribution | Impact |

| Conquest of Three Qins | Secured strategic base in Guanzhong |

| Northern Campaigns | Expanded territory, gained resources and manpower |

| Psychological Warfare Tactics | Enhanced effectiveness of smaller forces against larger enemies |

| Military Organization | Improved speed and coordination of Han armies |

The Downfall of Han Xin

Despite Han Xin’s significant contributions to the founding of the Han Dynasty, his relationship with Emperor Liu Bang became increasingly strained. Liu Bang, fearing Han Xin’s growing influence and military prowess, gradually reduced his authority. In late 202 BCE, Han Xin was demoted from his position as King of Chu to the lower rank of Marquis of Huaiyin. This demotion marked the beginning of Han Xin’s fall from grace and highlighted the growing political tensions between him and the emperor.

Recognizing the precarious nature of his position, Han Xin adopted a cautious approach. He claimed to be ill and stayed at home most of the time to reduce Liu Bang’s suspicions. This self-imposed isolation, while intended to alleviate tensions, may have inadvertently made Han Xin more vulnerable to his political enemies.

In 197 BCE, Han Xin’s downfall was set in motion when he met with Chen Xi, the Marquis of Yangxia, before Chen’s departure for Julu. During this meeting, Han Xin allegedly promised to aid Chen Xi from inside the capital if Chen were to start an uprising against the Han dynasty. This conversation would later be used as evidence of Han Xin’s involvement in a conspiracy against the throne.

The situation escalated when one of Han Xin’s household servants offended him, leading to the servant’s punishment. In retaliation, the servant’s young brother reported Han Xin’s alleged desire to rebel to Empress Lü Zhi. This accusation provided the pretext needed for Han Xin’s enemies to move against him.

Han Xin’s fate was sealed in early 196 BCE when Empress Lü Zhi and Xiao He devised a plan to lure him into a trap. They fabricated a story about Liu Bang’s return from suppressing Chen Xi’s rebellion and invited Han Xin to a celebratory feast at Changle Palace. Xiao He, using his influence, persuaded Han Xin to attend the event.

Upon arriving at Changle Palace, Han Xin was immediately seized, bound, and executed on Empress Lü Zhi’s orders. The swiftness and brutality of his execution underscore the political dangers of the time. Following Han Xin’s death, Empress Lü Zhi ordered the extermination of his entire clan, a common practice to prevent future retribution.

| Year (BCE) | Event |

| 202 | Demotion from King of Chu to Marquis of Huaiyin |

| 197 | Meeting with Chen Xi, alleged promise of support for rebellion |

| 196 | Accused of conspiracy, lured to Changle Palace and executed |

Final Thoughts

As I reflect on Han Xin’s life, I’m struck by the bittersweet irony of his fate. This military prodigy, who expanded territories and reformed armies, ultimately fell victim to the very political machinations he had helped navigate. His execution in 196 BCE marks a tragic end to a life filled with unparalleled achievements. Yet, even in his downfall, Han Xin’s story continues to captivate and inspire. His journey from a starving youth to the pinnacle of military leadership, and then to his untimely demise, serves as a stark reminder of the volatile nature of power in ancient China.